Every few months, it seems, academic Twitter gets itself all aflutter about marginalia. Mostly, these debates revolve around how we – as researchers, teachers, and writers – treat our books.

Some researchers are horrified by the very thought of writing in a book (even though these same researchers take highlighters, coloured pens, pencils, and stickers to journal articles). For these researchers, marginalia defaces books; it is disrespectful to the text and to the book as a material object.

Others see it as part of a necessary conversation with the work they are reading. Marginalia, for them, is a way to note their engagement with ideas, words, thoughts, and a way for them to start to work through their responses to what they’re reading. Sometimes those responses are mini-dissertations that wind along the margins of the page. Other times, they might be nothing more than exclamation marks or happy faces or stars – shorthand that is meaningful only to those who made the marks themselves.

It’s probably not at all surprising that I love marginalia. Marginalia is all about stories. In fact, as that point of encounter between a text and its readers, marginalia can sometimes be the heartof the story.

During the years that I worked with a large collection of letters written Samuel Auguste Tissot, one of the most celebrated physicians in eighteenth-century Europe, I encountered a few letters with marginalia. One, in particular, stood out. The main body of the letter was written by a medical professional or caregiver, and it outlined the patient’s condition and daily experiences. But the patient had her own meanings and understandings, and at various points, she interjected, adding information and/or contradicting what the caregiver/doctor had written. The interplay between these two voices – and two styles of handwriting – was the most interesting aspect of the letter. In these commentaries – both their content and their style – I was able to learn about the relationship between these two individuals, but also about the relationship that they were hoping to develop with the doctor.

Sometimes, however, marginalia is obscure, challenging. But to me, this only adds to its allure. Years ago, a friend of mine borrowed a book from one of her graduate supervisors. If I recall, it was something by Jacques Derrida, a notoriously challenging French philosopher. She was struggling her way through it, growing more and more baffled the more she read. Just when she was about to give up, she turned the page and saw that her supervisor had written a giant question mark, in red ink, across the entire page. The margins weren’t enough to contain the supervisor’s own bafflement. For my friend, this question mark was not only a vindication and a relief, but also a moment of solidarity: we’re in this together, that question mark said. And we’re going to be just fine.

At other times, marginalia is the only story. A number of years ago, I heard a conference presentation about Katie Gliddon, a suffragette who spent a period of time in Holloway Prison. She wasn’t allowed to have pencil and paper, or even books, in prison but somehow she managed to smuggle both in: a copy of The Poetical Works of Percy Bysshe Shelleyand pencils that she’d sewed into the hem of her skirt. In the abundant margins of this book of poetry, she proceeded to secretly write her autobiography in the form of a prison diary that also included drawings, a unique testament that gives us insight into the lives of everyday women fighting for women suffrage in the early part of the twentieth century (you can see parts of her diary here) .

Given that I love reading marginalia, perhaps it’s also not surprising that I deface my own books, scribbling in the margins, bending page corners, underlining words, adding stars and arrows. Much to the horror of some other academics, I make all of my books fully my own.

Over the years, I’ve convinced myself that this is because I love the archives. Because I love stories. Because I want to know more about how people before me thought, how they felt, how they imagined. And because in writing in my own books, I’ll contribute to the archives of the future: what stories might others find in my almost illegible scratchings?

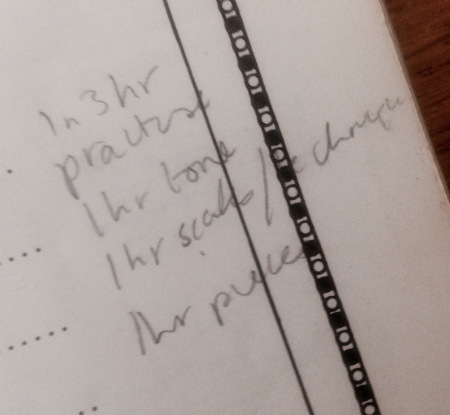

But just yesterday, as I was reading about the (re)appearance of Glenn Gould’s recording score for his 1981 Goldberg Variations, I wondered if my love of marginalia might have another origin. As I looked at the scans of these scrawled up pages, I thought about my own scrawled up pages, and about what it means to make music. If the score is, indeed, a point of encounter between composer and performer as I’ve been told, then it stands to reason that a conversation starts there. That conversation is intimate, it’s visceral, it’s ongoing. It’s in the notes we play (or sing), but it’s also in how we engage with the musical text itself: in the comments, signs, symbols, and markers that we add to the text as we make meaning of what’s presented to us.

A pristine score is a museum piece. It doesn’t live. It doesn’t breathe. It is static, waiting until a musician is ready to breathe life into it.

A marked-up, scrawled over musical score, by contrast, is a working score. It is evidence of that encounter between composer and performer in action. A marked-up, scrawled over score is a living score, a breathing score.

It is also a storytelling score.

As I look through my own marked up, scrawled over musical scores, I can follow my musical training and the development of my musical ideas. I can also follow my anxieties and my frustrations. If I put them all together, they would stand as the autobiography of my musical life.

© Sonja Boon, 2019